Celebrating SPICE’s 50th: SPICE’s Roots in the Bay Area China Education Project (BAYCEP)

Celebrating SPICE’s 50th: SPICE’s Roots in the Bay Area China Education Project (BAYCEP)

BAYCEP was the predecessor program to SPICE, which was established 50 years ago in 1976.

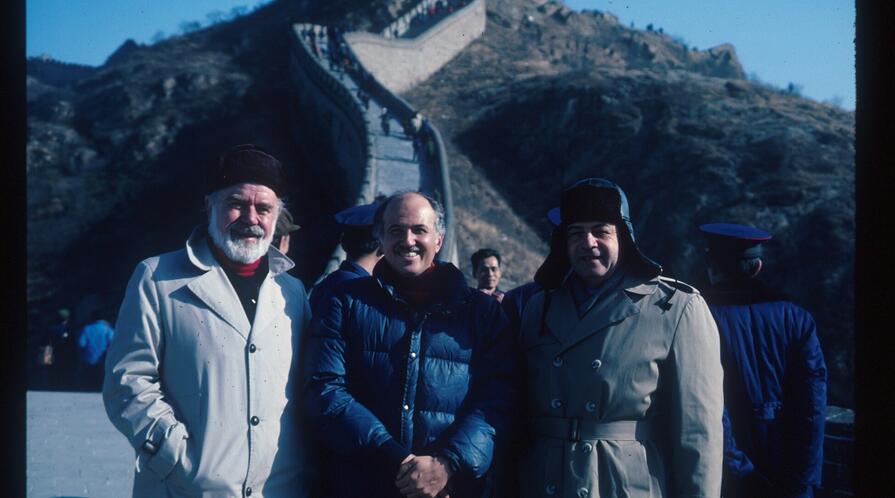

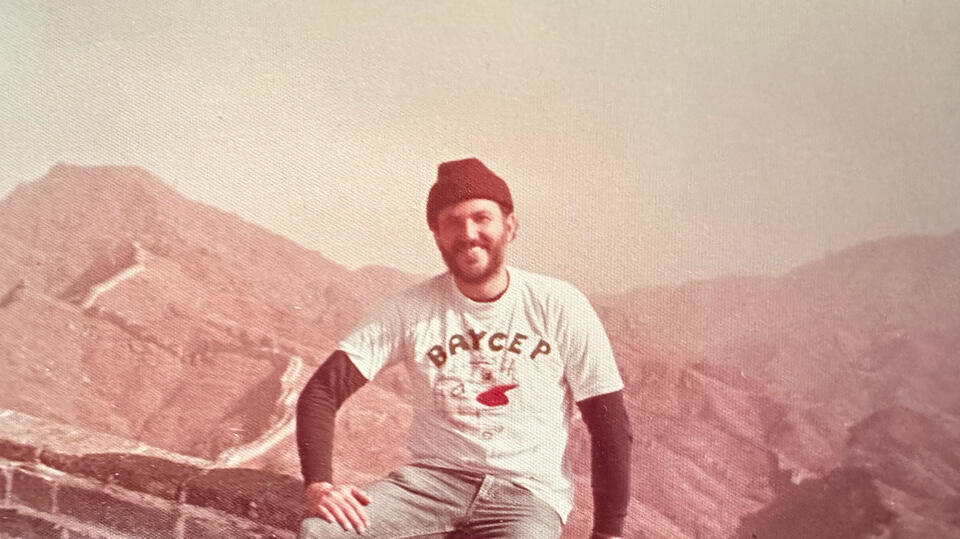

This article was written by Dr. David Grossman, founding Director of BAYCEP and SPICE, and draws on a conference paper that he presented in 1978. The updated excerpt and photos (taken in 1974 in the People's Republic of China) were reprinted with permission from Dr. Grossman. Dr. Grossman was the Director of SPICE from 1976 to 1988. This is the first of several articles—focusing on the 50-year history of SPICE—that will be posted this year.

Prior to World War II, the systematic study of Asia in American schools was rare. Studies of school textbooks found that the few references to Asia were marked by paternalism and stereotypes at best, and by racism and imperialist assumptions at worst. Following U.S. involvement in World War II and the Korean War, there was a notable increase in Asian studies at the collegiate level. At the pre-collegiate level, however, this growing attention to Asia was largely reflected in the addition of a Cold War dimension to the civics curriculum. In this context, China was typically studied as a geopolitical adversary, portrayed even more negatively than the Soviet Union.

In February 1972, a dramatic shift occurred in the tone of U.S.–China relations as a result of President Richard Nixon’s surprise visit to China. This watershed moment generated a surge in public demand for more current and reliable information about China and created new opportunities for reconsidering how China might be taught in American schools.

While the roots of the Bay Area China Education Project (BAYCEP) can be traced to earlier initiatives, the pivotal moment in its development was the June 1972 Wingspread Conference, “China in the Schools: Directions and Priorities.” Previous meetings addressing China education had been convened by professional organizations such as the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), but what distinguished the Wingspread Conference was its timeliness. The three sponsoring organizations—the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations, the Center for War/Peace Studies, and the Johnson Foundation—shared a widely held belief that the moment was ripe for a focused effort to improve education about China in American schools.

One of the central themes of the Wingspread discussions was a critique of prevailing models of scholar–teacher interaction, particularly the assumption that scholars should serve merely as visiting lecturers. Conference participants urged China scholars to become more attentive to the needs of teachers and school systems and to conceive of their work as part of a reciprocal, two-way process. In perhaps the most influential proposal to emerge from the conference, Yale historian Jonathan Spence called for the development of a cohort of “scholar consultants” who would be both substantively knowledgeable and pedagogically sensitive. This idea would become a cornerstone of BAYCEP.

Ultimately, BAYCEP was the only program to emerge directly from the Wingspread Conference. As early as August 1972, Stanford professor John Lewis convened a meeting of San Francisco Bay Area educators and scholars focused on “Teaching China in the Schools.” This group subsequently submitted a proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities under the auspices of the National Committee on U.S.–China Relations. The proposal was successfully funded and outlined a pilot project designed to strengthen humanities teaching in Bay Area schools by creating new mechanisms of cooperation between university scholars and pre-collegiate educators. It emphasized the educational value of Chinese history, society, and culture for enhancing multicultural education and sought to organize locally available resources on China through consultancy relationships, training programs, and curriculum materials that could later be adapted for use in other communities and fields of study.

The transition from this broad mission statement to a fully functioning program was not linear. Stakeholders debated the project’s target audience, the selection of appropriate content, and staff qualifications. Acceptance of a China-focused initiative in schools was by no means assured; at one point, a district superintendent rejected participation on the grounds that the project constituted “Communist propaganda.” The underlying challenge was to design a China-focused program that was both curriculum-relevant and pedagogically sound.

In this regard, BAYCEP’s most innovative component was the development of an associate, or “scholar intern,” program intended to strengthen links between universities and schools. Graduate students and recent graduates in Chinese studies or related education programs were appointed as project associates. These associates underwent intensive training and mentoring to familiarize them with effective pre-collegiate teaching methods and available instructional resources, which were notably scarce at the time. They then worked directly with teachers through professional development workshops, helping translate scholarly knowledge into classroom practice.

Although BAYCEP was not initially conceived as solely a curriculum development project, the need for instructional materials soon became apparent. In collaboration with university scholars and classroom teachers, the project first produced guides to recommended resources on China. As these guides proved necessary but insufficient, BAYCEP later developed instructional units on topics such as the Chinese language, family life, education, sports, and stereotyping. As with the professional development workshops, careful attention was given to both substantive content and pedagogical effectiveness.

True to its original mission, BAYCEP emerged as a model for linking university scholarship with pre-collegiate education. In subsequent years, parallel projects focusing on Japan, Latin America, Africa, and Eastern and Western Europe were initiated. Together with BAYCEP, these initiatives were brought under a common umbrella in 1976, enabling collaboration and cross-fertilization across area studies. This umbrella program—the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education (SPICE)—continues to operate to this day.

Beyond its immediate contributions to China education, BAYCEP’s enduring legacy lies in its redefinition of the relationship between universities and pre-collegiate schools. By institutionalizing the role of the scholar consultant and embedding graduate students and recent graduates within K–12 professional development, BAYCEP moved beyond episodic outreach toward a sustained, collaborative model of knowledge exchange. Its emphasis on pedagogical relevance, mutual learning, and curriculum integration anticipated later approaches to public scholarship and teacher professionalization in area studies. The success of BAYCEP also demonstrated that international and cross-cultural education could be both academically rigorous and responsive to local educational contexts, even amid political uncertainty. As the foundational program within what became SPICE, BAYCEP served not only as a prototype for subsequent regional initiatives but also as a durable model for translating university-based scholarship into meaningful educational practice—an approach that continues to shape international education well beyond its original historical moment.

To stay informed of SPICE news, join our email list and follow us on Facebook, X, and Instagram.