Educating the Next Generation: SPICE Perspectives on China and Japan

TheStanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education (SPICE) develops innovative materials on key issues in international affairs for K-14 students in the United States and independent schools abroad. Multidisciplinary SPICE materials serve as a bridge between classrooms of receptive students and teachers and FSI scholars and collaborative partners. SPICE offered a number of important new publications for an emerging generation of scholars this year.

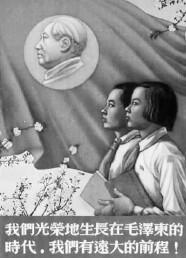

As with all SPICE projects, collaboration with scholars and other experts on the Cultural Revolution was essential to the development of this unit. Andrew G. Walder, former director of the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, served as principal advisor and was instrumental in the conceptualization of the curriculum. Connie Chin of Stanford’s Center for East Asian Studies translated entries from a Chinese textbook that students compare with textbooks of Taiwan and the United States. Jiang, a local author and survivor of the Cultural Revolution, oversaw the development of a lesson that features her book, Red Scarf Girl. Jiang worked with many Chinese who provided their own memoirs of the Cultural Revolution for the curriculum, exposing students to first-hand experiences of Chinese youth during this time.

Another new SPICE unit, titled Tea and the Japanese Tradition of Chanoyu, results from a collaboration with the Urasenke Foundation of Kyoto, Japan. This unit traces the history of tea from its origins in China 5,000 years ago to modern times, with an emphasis on its prominent role in Japan. By the 16th century, Japan’s tea practice had become formalized by Sen Rikyu, who integrated art, religion, social interaction, and economics into his tea practice. He so revolutionized chanoyu that he is universally recognized as the most important tea master who ever lived. The Urasenke School of Tea was established by one of his descendants some 400 years ago, and the Sen family has continued to pass on its way of tea for 16 generations.

SPICE worked with two of Sen Rikyu’s descendants, Great Grand Master Sen Soshitsu XV and Grand Master Sen Soshitsu XVI Iemoto, to develop this unit. Each wrote a personal letter, expressing their excitement about introducing American students to a cherished Japanese tradition. Grand Master Sen Soshitsu XVI Iemoto says, “In the age of globalization, there is a great need for truly international people, that is, those who understand and appreciate their own culture as well as that of others, and those who value both the diversity of mankind and the universality of the human spirit. These are the people who will enrich and reinvigorate our global society in the future.” His father, Great Grand Master Sen Soshitsu XV, adds, “I am very happy to have been involved with this project which, I pray, will help to contribute to world peace and goodwill through my motto ‘Peacefulness through a Bowl of Tea.’”